The Mystery of a Hansom Cab

Melbourne in the mid 1880s was a bustling place. Thanks to the goldrush, it had already spent 20 years as Australia largest city, even if it was only half the age of Sydney.

Herds of cattle were still occasionally shepherded through the wide streets, but for the most part Melbourne had moved on from its agricultural beginnings and it was now a proper city with a skyline dominated by church spires and belching chimneys, and was connected to other colonial centres courtesy of regular rail and stage coach services, and linked to the rest of the globe thanks to a steady stream of sailing ships.

The city’s famous tram network was however yet to be established, and if you wanted to get around town, particularly in wet weather or for journeys of more than a few city blocks, you might find yourself needing to hail a cab. Not a taxicab in the modern sense – motor cars were still a way off – but a hansom cab.

The hansom cab was a simple two-wheeled horse-drawn carriage. It was small and light, usually accommodating just two passengers. The driver sat high, behind the enclosed carriage, and took charge of the single horse. Passengers could speak with him via a small trapdoor, but otherwise they were securely tucked away from his prying eyes and could get up to anything. Even murder.

And it was this premise that formed the basis of the biggest selling crime novel of the nineteenth century, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab.

Written and set in Melbourne by Fergus Hume and first published in 1886, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab was a massive success, selling around three quarters of a million copies in Hume’s lifetime. Even Sherlock Holmes, who made his debut a year later, couldn’t match the early sales.

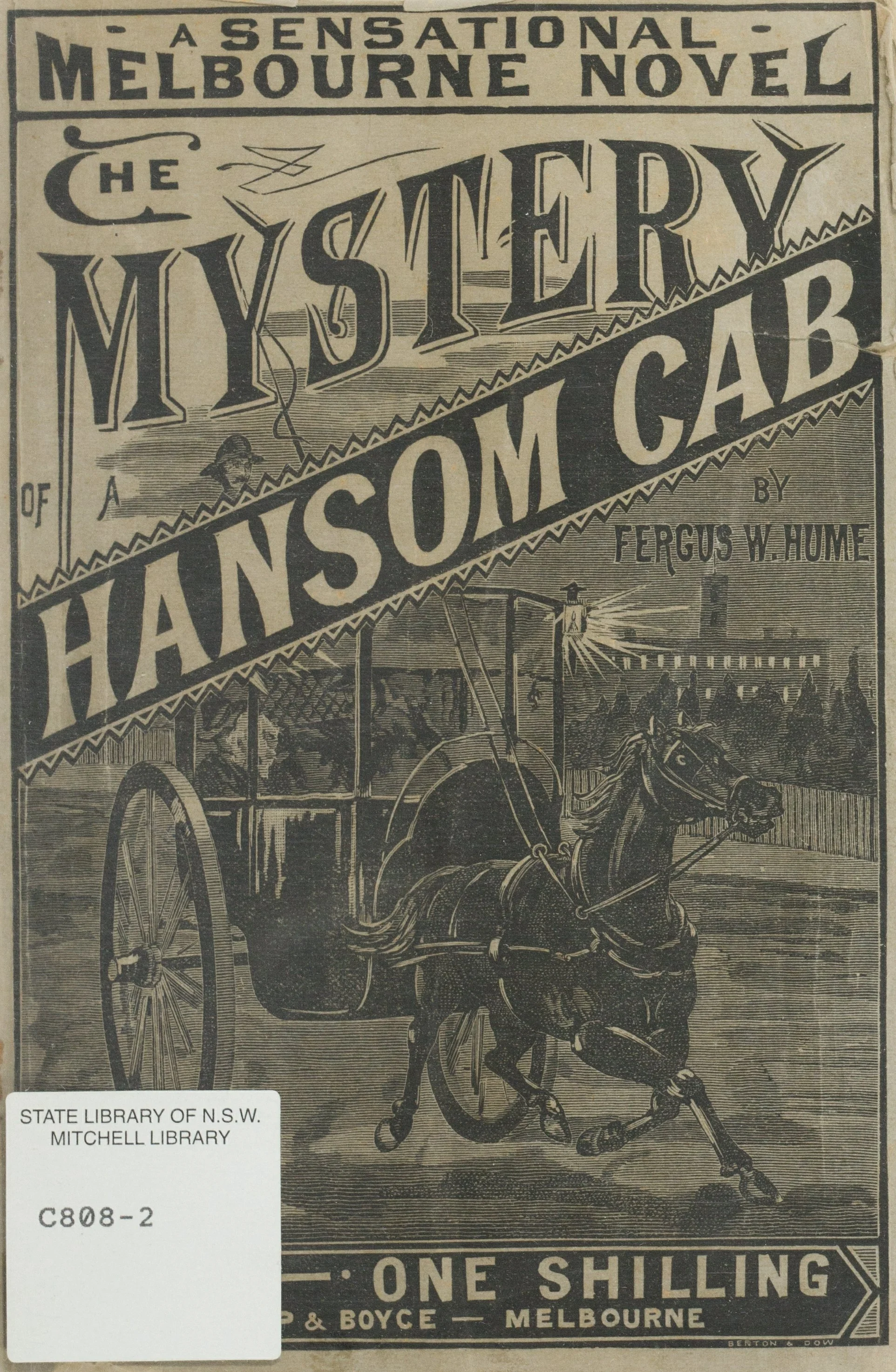

Cover of the first Australian edition of The Mystery of a Hansom Cab

Later editions printed in London sold in the hundreds of thousands, but often toned down some of the language and omitted local details.

Image courtesy of State Library NSW

Set against the backdrop of a young city full of opportunists and hopefuls, it paints a picture of a growing Melbourne fighting to balance its vice with virtue. Class divides are painfully evident, and the depictions of the slums of Little Bourke Street and the exclusive Melbourne Club provide a glimpse into what life was like here for many of the city’s inhabitants 140 years ago.

Collins Street, with its impressive banks and boutiques, had already become established as the place to be seen, and Hume’s description of the upper classes ‘doing the Block’ are witty and insightful.

As the sun brings out bright flowers so the seductive influence of the hot weather had brought out all the ladies in gay dresses of innumerable colours, which made the long street look like a restless rainbow.

And he goes on the flesh out the scene further:

Carriages were bowling smoothly along, their occupants smiling and bowing as they recognised their friends on the sidewalk; lawyers, their legal quibbles finished for the week, were strolling leisurely along, with their black bags in their hands; portly merchants, forgetting Flinders Lane and incoming ships, were walking beside their pretty daughters, and the representatives of swelldom were stalking along in their customary apparel of curly hats, high collars, and masher suits. Altogether it was a very pleasant and animated scene…

The plot contains all the twists and turns expected of any good detective story and readers are left guessing whodunnit until almost the very end. Hume went on to write at least another 130 novels, though none were to match the success of his first.

Today, when I find myself on the corner outside Scots’ Church where the opening scene of the novel takes place, it’s easy to imagine a hansom cab pulling up to pick up a couple of young men, a little worse for wear, after a big night on the town. No doubt this scene played out countless times in reality, ending with the passengers’ safe delivery home. In Hume’s fictional world however, it’s one that ended in a shocking murder and gave the book reading public a ripping yarn.